Climate and science reporter, BBC News

Nipah Dennis/Bloomberg/Getty Images

Nipah Dennis/Bloomberg/Getty ImagesPlastic production has exploded in the last century – to some it has been a miracle product while to others it is a pollution nightmare.

Scientists have estimated that there are nearly 200 trillion pieces floating in the world’s oceans, and this could triple if no action is taken.

In 2022, countries agreed to develop a legally binding global treaty to cut the waste and the harmful chemicals some plastics contain – but after two years no agreement has been reached.

On Tuesday, the world’s nations meet again at a UN conference in Geneva – could they finally agree how to curb the plastic excesses?

Why is plastic such a valuable product?

Human societies have used plastics that occur naturally in the environment for hundreds of years, in the form of rubber, horn and shellac.

But the 20th Century brought the explosion of synthetic plastics, made from processing fossil fuels.

The material’s versatility, strength and heat-resistant properties has lent itself to thousands of uses, from sewage pipes to life-saving medical equipment, to clothing.

It has become ubiquitous in a short time without understanding its full impact, explains Dr Alice Horton, research scientist at the National Oceanography Centre.

“Proportional to life on earth, plastics have been around for no time at all, there are people alive that weren’t using plastics as children. I think that’s what makes this quite a concerning material,” said Dr Horton.

“It has exploded in such a way that we are using it in every application in our lives and yet we are suddenly realising there may be problems with it.”

How are plastics impacting our planet?

Levels of plastic production have grown exponentially over the last few decades. In 1950 two million tonnes was produced, by 2022 that had risen to 475 million tonnes.

Although plastic can be reused, the cost and availability of recycling infrastructure means very little is. About 60% of all plastics are single use and just 10% are estimated to be recycled, according to analysis in Nature.

Plastic has been shown to accumulate in the marine environment where it poses particular problems for wildlife who can ingest it.

“They can confuse it as food, which then harms their internal organs and also can lead to fatalities, because of digestion difficulties,” said Zaynab Sadan, global plastics policy lead at WWF.

She said they could also become entangled in discarded fishing gear or plastic packaging that has entered the ocean from sewage systems.

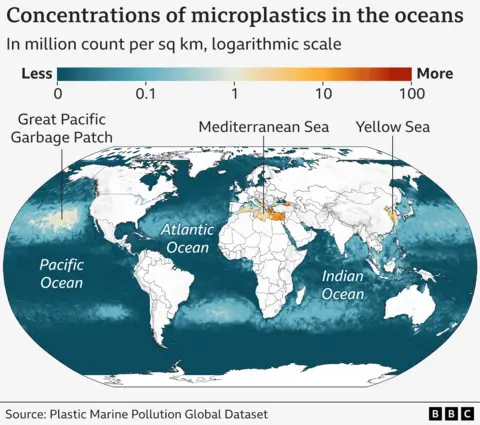

When it enters the environment, most plastic breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces – known as microplastics. They have been found across all geographical ranges, from the deep sea to mountain tops, and across all living systems ever tested.

Research is continuing to understand the full impact, with different species faring better than others. But Dr Horton from the National Oceanography Centre warns there is a threshold where animals will start to be harmed.

“When we [get] accumulation of plastic in tissues we start seeing inflammation, cell damage, hormonal changes. Things that are not outright going to kill an organism but likely to have this accumulative, long-term effect whereby they get weaker and weaker, and sicker and sicker, and either become diseased or die,” she explained.

Are plastics harmful for us?

Plastics are a “grave, growing and under-recognised danger” for human health, according to a new expert report.

The Lancet Countdown estimated that health-related disease and death from the “plastic crisis” is responsible for at least $1.5tn (£1.1tn) a year in health-related damages.

Gerald Anderson/Anadolu/Getty Images

Gerald Anderson/Anadolu/Getty ImagesThese impacts can range from air pollution from the production of plastic, through to elevated risk of cancer, respiratory illnesses and miscarriages from plastic contamination in our bodies.

Plastics contain more than 16,000 chemicals such as dyes and flame retardants, some of which are toxic and cancer-causing.

Despite the growing body of evidence of the hazards of plastic, the Lancet report highlights that there is a lack of transparency as to what is in most products. Just a quarter of plastic chemicals have data on their impact, but of those tested 75% were found to be “highly hazardous”.

What are countries trying to agree?

In 2022, countries agreed a global treaty was needed in two years to tackle the issue.

That deadline passed in December 2024, after five rounds of negotiations, with no treaty having been signed.

On Tuesday, more than 170 nations will meet again to try to get a deal over the line.

The main issues they are trying to get agreement on include:

- Targets on cutting the production levels of single-use plastics

- Bans on some of the most harmful chemicals in plastic

- Universal guidance on the design of plastic products

- Financing of this effort

Products that have to meet consistent design standards can help to improve recycling, save costs and reduce the demand for virgin plastics, Rob Opsomer, executive lead of plastics and finance at the Ellen McArthur Foundation, which co-convenes the Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty, told the BBC.

“So, to give you one example, a drinks bottle, if it is coloured, the value of what you can get from it if you sell the recycled material is half the value of a clear, uncoloured bottle,” he explained.

Nearly 100 countries, including the UK, are calling for an “ambitious” treaty which would include a commitment to limit production levels. But there has been strong opposition from a group of oil-producing nations including Russia and Saudi Arabia who want the talks to focus not on producing less, but recycling more.

Demand for oil in global energy and transport systems is expected to peak in the next few years as countries move to greener technologies. This could leave plastic as one of the few growth markets for the oil industry. Any efforts to limit production could pose short term economic damage to the petrostates.

But for those users of plastics not having clear, global regulations is costing them.

“It is a fundamental risk. Businesses don’t want packaging with their brand name on it to be littering the streets and our oceans,” said Mr Opsomer.

He said there was also the cost for businesses of having to comply with hundreds of new standards globally every year on plastics.

The Business Coalition, which includes some of the biggest global users of plastic such as Nestle and Unilever, is calling for governments to introduce coordinated taxes on their businesses to help pay for the cost of recycling and cleaning up plastic waste.

What can you do to reduce plastic waste?

Single-use plastic is the biggest contributor to plastic waste in the environment, and most of our daily consumption of this comes from food packaging.

You can take a reusable container or cup if you are getting a takeaway, and when food shopping consider taking a reusable sealed bag to weigh your fruit and vegetables.

It is estimated that more than a quarter of microplastics in the environment come from car tyres. For those that are able, walking and cycling to the local shops or sharing car journeys with friends or neighbours can help.

And avoid plastics that break down to microplastics more easily – such as chewing gum and glitter. There are many non-plastic alternatives still available which means you can keep having fun at festivals.

#Summit #opens #final #push #plastics #treaty #tackle #crisis