An international team of astronomers on Wednesday unveiled the most compelling evidence to date that dark energy — a mysterious phenomenon pushing our universe to expand ever faster — is not a constant force of nature but one that ebbs and flows through cosmic time.

Dark energy, the new measurement suggests, may not resign our universe to a fate of being ripped apart across every scale, from galaxy clusters down to atomic nuclei. Instead, its expansion could wane, eventually leaving the universe stable. Or the cosmos could even reverse course, eventually doomed to a collapse that astronomers refer to as the Big Crunch.

The latest results bolster a tantalizing hint from last April that something was awry with the standard model of cosmology, scientists’ best theory of the history and the structure of the universe. The measurements, from last year and this month, come from a collaboration running the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument, or DESI, on a telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona.

“It’s a bit more than a hint now,” said Michael Levi, a cosmologist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the director of DESI. “It puts us in conflict with other measurements,” Dr. Levi added. “Unless dark energy evolves — then, boy, all the ducks line up in a row.”

The announcement was made at a meeting of the American Physical Society in Anaheim, Calif., and accompanied by a set of papers describing the results, which are being submitted for peer review and publication in the journal Physical Review D.

“It’s fair to say that this result, taken at face value, appears to be the biggest hint we have about the nature of dark energy in the ~25 years since we discovered it,” Adam Riess, an astrophysicist at Johns Hopkins University and the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore who was not involved in the work but shared the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics for discovering dark energy, wrote in an email.

But even as the DESI observations challenged the standard model of cosmology, which predicts that dark energy is constant across time, a separate result has reinforced it. On Tuesday, the multinational team that ran the Atacama Cosmology Telescope in Chile released the most detailed images ever taken of the infant universe, when it was a mere 380,000 years old. (That telescope was decommissioned in 2022.)

Their report, not yet peer-reviewed, seems to confirm that the standard model was operating as expected in the early universe. One element in that model, the Hubble constant, describes how fast the universe is expanding, but over the last half-century measurements of the constant have starkly disagreed, an inconsistency that today has shrunk to about nine percent. Theorists have mused that perhaps an additional spurt of dark energy in the very early universe, when conditions were too hot for atoms to form, could resolve this so-called Hubble tension.

The latest Atacama results seem to rule out this idea. But they say nothing about whether the nature of dark energy might have evolved later in time.

Both reports evoked effusive praise from other cosmologists, who simultaneously confessed to a cosmic confusion about what it all meant.

“I don’t think much is left standing as far as good ideas for what might explain the Hubble tension at this point,” said Wendy Freedman, a cosmologist at the University of Chicago who has spent her life measuring the universe and was not involved in either study.

Michael Turner, a theorist at the University of Chicago, who was also not involved in the studies, said: “The good news is, no cracks in the cosmic egg. The bad news is, no cracks in the cosmic egg.”

Dr. Turner, who coined the term “dark energy,” added that if there was a crack, “it has not opened wide enough — yet — for us to clearly see the next big thing in cosmology.”

Astronomers often compare galaxies in an expanding universe to raisins in a baking cake. As the dough rises, the raisins are carried farther apart. The farther they are from each other, the faster they separate.

In 1998, two groups of astronomers measured the expansion of the universe by studying the brightness of a certain type of supernova, or exploding star. Such supernovas generate the same amount of light, so they appear predictably fainter at farther distances. If the expansion of the universe were slowing, as scientists believed at the time, light from faraway explosions should have appeared slightly brighter than foreseen.

To their surprise, the two groups found that the supernovas were fainter than expected. Instead of slowing down, the expansion of the universe was actually speeding up.

No energy known to physicists can drive an accelerating expansion; its strength should abate as it spreads ever more thinly across a ballooning universe. Unless that energy comes from space itself.

This dark energy bore all the earmarks of a fudge factor that Albert Einstein inserted into his theory of gravity back in 1917 to explain why the universe was not collapsing under its own weight. The fudge factor, known as the cosmological constant, represented a kind of cosmic repulsion that would balance gravity and stabilize the universe — or so he thought. In 1929, when it became clear that the universe was expanding, Einstein abandoned the cosmological constant, reportedly calling it his biggest blunder.

But it was too late. One feature of quantum theory devised in 1955 predicts that empty space is foaming with energy that would produce a repulsive force just like Einstein’s fudge factor. For the last quarter-century, this constant has been part of the standard model of cosmology. The model describes a universe born 13.8 billion years ago, in a colossal spark known as the Big Bang, and composed of 5 percent atomic matter, 25 percent dark matter and 70 percent dark energy. But the model fails to say what dark matter or dark energy actually are.

If dark energy really is Einstein’s constant, the standard model portends a bleak future: The universe will keep speeding up, forever, becoming darker and lonelier. Distant galaxies will eventually be too far away to see. All energy, life and thought will be sucked from the cosmos.

‘Something to go after’

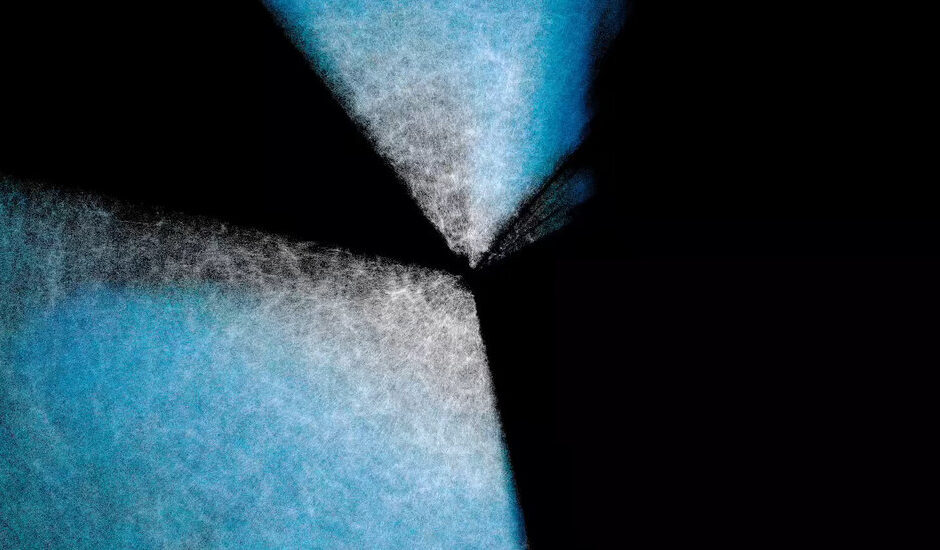

Astronomers on the DESI team are trying to characterize dark energy by surveying galaxies in different eras of cosmic time. Tiny irregularities in the spread of matter across the primordial universe have influenced the distances between galaxies today — distances that have expanded, in a measurable way, along with the universe.

Data used for the latest DESI measurement consisted of a catalog of nearly 15 million galaxies and other celestial objects. Alone, the data set does not suggest that anything is awry with the theoretical understanding of dark energy. But combined with other strategies for measuring the expansion of the universe — for instance, studying exploding stars and the oldest light in the universe, emitted some hundred thousand years after the Big Bang — the data no longer lines up with what the standard model predicts.

Enrique Paillas, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Arizona who announced the DESI measurement publicly on Wednesday, noted that the data imply that the cosmic acceleration driven by dark energy began earlier in time, and is currently weaker, than what the standard model predicts.

The discrepancy between data and theory is at most 4.2 sigma (in the units of uncertainty preferred by physicists), representing one in 50,000 chances that the results are a fluke. But the mismatch is not yet at five sigma (equal to one in 3.5 million chances), the stringent standard set by physicists to claim a discovery.

Still, the disconnect is enticingly suggestive that something in the cosmological model is not well understood. Scientists might need to revise how they interpret gravity or make sense of the ancient light from the Big Bang. DESI astronomers think the problem could be the nature of dark energy.

“If we introduce a dynamical dark energy, then the pieces of the puzzle fit together better,” said Mustapha Ishak-Boushaki, a cosmologist at the University of Texas at Dallas who helped lead the latest DESI analysis.

Will Percival, a cosmologist at the University of Waterloo in Ontario and a spokesperson for the DESI collaboration, expressed excitement about what lies on the horizon. “This is actually a little bit of a shot in the arm for the field,” he said. “Now we’ve got something to go after.”

In the 1950s, astronomers claimed that only two numbers were needed to explain cosmology: one related to how fast the universe was expanding and another describing its deceleration, or how much that expansion was slowing down. Things changed in the 1960s, with the discovery that the universe was bathed in light from the Big Bang, known as the cosmic microwave background. Measuring this background radiation allowed scientists to investigate the physics of the early universe and the way that galaxies subsequently formed and evolved. As a result, the standard model of cosmology now requires six parameters, including the density of both ordinary and dark matter in the universe.

As cosmology has become more precise, additional tensions have arisen between predicted and measured values of these parameters, leading to a profusion of theoretical extensions to the standard model. But the latest results from the Atacama Cosmology Telescope — the clearest maps to date of the cosmic microwave background — seem to slam the door on many of these extensions.

DESI will continue collecting data for at least another year. Other telescopes, on the ground and in space, are charting their own views of the cosmos; among them are the Zwicky Transient Facility in San Diego, the European Euclid space telescope and NASA’s recently launched SPHEREx mission. In the future, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will begin recording a motion picture of the night sky from Chile this summer, and NASA’s Roman Space Telescope is set to launch in 2027.

Each will soak up the light from the sky, measuring pieces of the cosmos from different perspectives and contributing to a broader understanding of the universe as a whole. All serve as ongoing reminders of just what a tough egg the universe is to crack.

“Each of these data sets comes with its own strengths,” said Alexie Leauthaud, a cosmologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a spokesperson for the DESI collaboration. “The universe is complicated. And we’re trying to disentangle a lot of different things.”

#Astronomers #Hint #Dark #Energy #Isnt #Thought