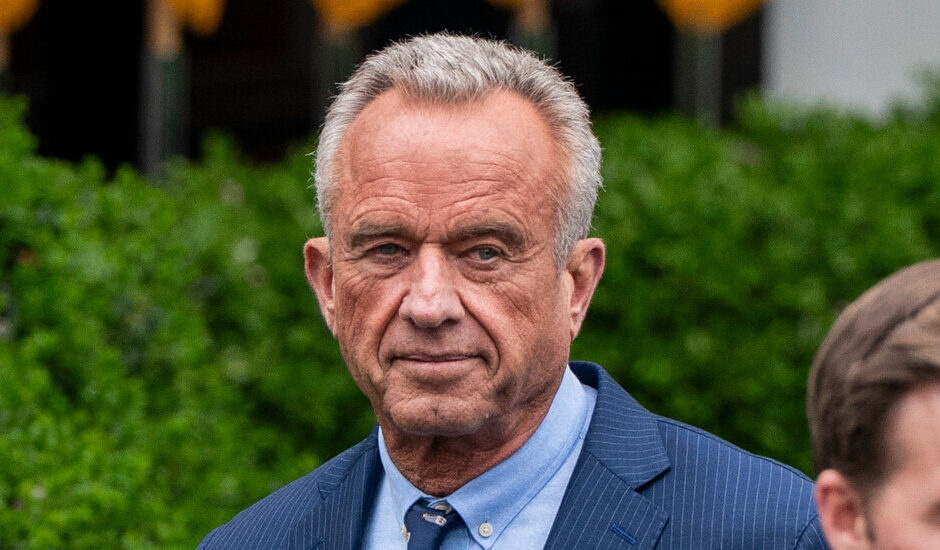

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has spoken of an “existential threat” that he said can destroy the nation.

“We have the highest chronic disease burden of any country in the world,” Mr. Kennedy said at a hearing in January before the Senate confirmed him as the secretary of Health and Human Services.

And on Monday he is starting a tour in the Southwest to promote a program to combat chronic illness, emphasizing nutrition and lifestyle.

But since Mr. Kennedy assumed his post, key grants and contracts that directly address these diseases, including obesity, diabetes and dementia, which experts agree are among the nation’s leading health problems, are being eliminated.

These programs range in scale and expense. Researchers warn that their demise could mean lost opportunities to address an aspect of public health that Mr. Kennedy has said is his priority.

“This is a huge mistake,” said Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, the co-director of the Healthcare Transformation Institute at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

Decades of Diabetes Research Discontinued

Ever since its start in 1996, the Diabetes Prevention Program has helped doctors understand this deadly chronic disease. The condition is the nation’s most expensive, affecting 38 million Americans and incurring $306 billion in one recent year in direct costs. With about 400,000 deaths in 2021, it was the eighth leading cause of death.

The program has been terminated, and the reason has little to do with its merits. Instead, it seems to be a matter of a lead researcher’s working in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The program began when doctors at 27 medical centers received funding from the National Institutes of Health for a study asking whether Type 2 diabetes could be prevented. The 3,234 participants had high risk of the disease.

The results were a huge victory. Those assigned to follow a healthy diet and exercise routine regularly reduced their chances of developing diabetes by 58 percent. Those who took metformin, a drug that lowers blood sugar, decreased their risk by 31 percent.

The program entered a new phase, led by Dr. David M. Nathan, a diabetes expert at Harvard Medical School. Researchers followed the participants to see how they fared without the constant attention and support of a clinical trial. The researchers also examined their genetics and metabolism and looked at measures of frailty and cognitive function.

Several years ago, the investigators had an idea. Some studies suggested that people with diabetes had a higher risk of dementia. But scientists didn’t know if it was vascular dementia or Alzheimer’s or what the precise risk factors were. The diabetes program could renew its focus on investigating this with its 1,700 aging participants.

The group added a new principal investigator, the dementia expert Dr. Jose A. Luchsinger. For administrative reasons, including the newfound focus on dementia, the program decided its money should flow through Dr. Luchsinger’s home institution, Columbia University, rather than through Harvard or George Washington University, where a third principal investigator works.

On March 7, the Trump administration cut $400 million in grants and contracts to Columbia, saying Jewish students were not protected from harassment during protests over the war in Gaza. The diabetes grant was among those terminated: $16 million a year that Columbia shared across 30 medical centers. The study ended abruptly.

Asked about the termination, Andrew G. Nixon, director of communications at Health and Human Services, provided a statement from the agency’s acting general counsel saying that “anti-Semitism is clearly inconsistent with the fundamental values that should inform liberal education” and that “Columbia University’s complacency is unacceptable.”

At the time their grant ended, the researchers had started advanced cognitive testing for evidence of dementia in patients, followed by brain imaging to look for amyloid, the hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. They planned to complete the tests during the next two years.

Then, Dr. Luchsinger said, the group was going to look at blood biomarkers of amyloid and other signs of dementia, including brain inflammation. For comparison, they planned to perform the same tests on participants’ blood samples from 7 and 15 years ago.

“Very few studies have blood collected and stored going that far back,” Dr. Luchsinger said.

Now much of the work cannot begin, and the part that had started remains incomplete.

Another troubling question the researchers hoped to answer was whether metformin increases, decreases or has no effect on the risk of dementia.

“This is the largest and longest study of metformin ever,” Dr. Luchsinger said. Participants assigned to take the drug in the 1990s took it for more than 20 years.

“We thought we had the potential to put to rest this question about metformin,” Dr. Luchsinger said.

The only ways to save the program, Dr. Nathan said, are for Mr. Kennedy to agree to restore the funding at Columbia or to transfer the grant to a principal investigator at another medical center.

The study investigators are appealing to the diabetes caucus in Congress, hoping it can help make their case to the Health and Human Services.

“We hope the congressmen and senators might prevail and say: ‘This is crazy. This is chronic disease. This is what you wanted to study,’” Dr. Nathan said.

So far, there has been no change.

Include Diversity. Actually, That’s Too Much Diversity.

Compared with the Diabetes Prevention Program, a program to train pediatricians to become scientists is tiny. But pediatric researchers say that the Pediatric Scientist Development Program helps ensure that chronic childhood diseases are included in medical research.

It began 40 years ago when chairs of pediatric departments called for the creation of the program, which has been continually funded ever since by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Participants are clinicians who were trained in subspecialties like endocrinology and nephrology, practiced as clinicians and were inspired to go into research to help young patients with the diseases they had seen firsthand.

The highly competitive program pays for seven to eight pediatricians to train at university medical centers for a year, pairing them with mentors and giving them time away from the clinic to research conditions including obesity, asthma and chronic kidney disease.

In retrospect, the program’s fate was sealed in 2021 when its leaders applied for a renewal of their grant. It seemed pro forma. This was its eighth renewal.

This time, though, an external committee of grant reviewers told the investigators their proposal’s biggest weakness was a lack of diversity. The program needed to seek pediatricians who represented diverse ethnicities, economic backgrounds, states, types of research and pediatric specialties.

The critique said, for example, that “attention must be given to recruiting applicants from diverse backgrounds, including from groups that have been shown to be nationally underrepresented in the biomedical, behavioral, clinical and social sciences.”

So the program’s leaders sprinkled diversity liberally through a rewritten grant application.

“Diversity, in its broadest sense, was all over the grant,” said Dr. Sallie Permar, professor and chairwoman of pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medical College and director of the program. “It was exactly what the reviewers appreciated when we resubmitted.”

The grant was renewed in 2023. Now it is terminated. The reason? Diversity.

The termination letter, from officials in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, said there was no point in trying to rewrite the grant request. The inclusion of diversity made the application so out of line that “no modification of the project could align the project with agency priorities.”

Mr. Nixon, the health department spokesman, did not reply to queries about the pediatric program’s cancellation.

Participants in the program are distraught.

Dr. Sean Michael Cullen had been studying childhood obesity at Weill Cornell in New York. He has investigated why male mice fed a high-fat diet produced offspring that became fat, even when those offspring were fed a standard diet.

He hoped his findings would help predict in humans which children were at risk of obesity so pediatricians could try to intervene.

Now the funds are gone. He may seek private or philanthropic funding, but he doesn’t have any clear prospects.

Dr. Evan Rajadhyaksha is in a similar situation. He’s a childhood kidney disease specialist at Indiana University. When he was a resident, he cared for a little girl who developed kidney disease because of a condition in which some urine washes up from the bladder into the kidneys.

Dr. Rajadhyaksha has a hypothesis that vitamin D supplementation could protect children with this condition.

Now, that work has to stop. Without funding, he expects to leave research and return to clinical work.

Dr. Permar said she hadn’t given up. The program costs only $1.5 million each year, so she and her colleagues are looking for other support.

“We are asking foundations,” she said. “We are starting to ask industry — we haven’t had industry funding before. We are asking department chairs and children’s hospitals, are they willing to fund-raise?”

“We are literally looking under every couch cushion,” Dr. Permar said.

“But,” she said, federal support for the program “has been the foundation and cannot be supplanted.”

#RFK #Champions #Chronic #Disease #Prevention #Key #Research #Cut