Investors around the globe this week sent President Trump a clear message about his new tariff policy, announced triumphantly as a remaking of the economic order.

They don’t like it.

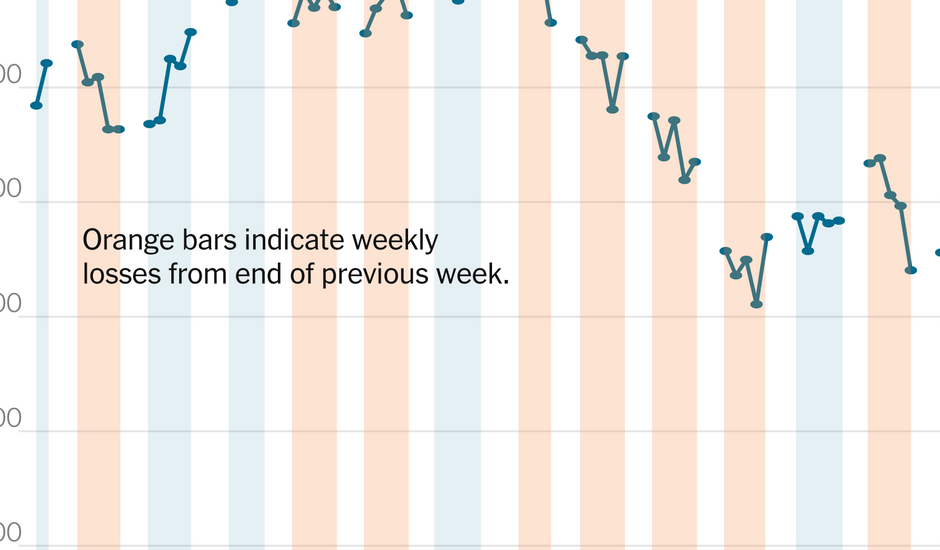

The S&P 500 fell 6 percent on Friday, bringing its losses for the week to 9.1 percent. Stocks hadn’t fallen this far this fast since the early days of the coronavirus pandemic — it was the steepest weekly decline since March 2020.

As then, the S&P 500 is quickly approaching bear market territory, a drop of 20 percent from the latest high and marks extreme pessimism among investors. By Friday, the index was down more than 17 percent from its February peak. The tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite and the Russell 2000 index of smaller companies, which are more sensitive to changes in the economic outlook, have both already fallen into a bear market. Around the world, stocks have tumbled.

But this meltdown wasn’t driven by the emergence of a new and deadly virus, or an unforeseen housing crisis like the one that wiped out stock values in 2007 and 2008 as it triggered the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

It was driven by a policy decision by the president.

“I hope that the message that the stock market is sending to the administration is being heard,” Ed Yardeni, a veteran market analyst, said in a television interview. “The market is giving a big thumbs down to this tariff policy.”

Analysts and market historians struggled to point to another time a president had directly inflicted so much damage on the financial markets. There are some recent parallels: An ill-timed budget proposal by Liz Truss, Britain’s prime minister in 2022, led to days of market chaos, and she had to resign within weeks.

But Mr. Trump has shown no interest in backing down. “MY POLICIES WILL NEVER CHANGE,” he wrote in a social media post on Friday.

So investors, economists and business leaders are hastily assessing the new and unprecedented policies and the economic damage that those policies could cause.

“We are just working through what this could possibly mean,” said Lindsay Rosner, head of multisector fixed-income investing at Goldman Sachs Asset Management. She added that the sheer scale of the tariffs “increases the probability of a recession.”

It’s a remarkable turn in sentiment. After Mr. Trump was elected, and in the first month of his administration, investors were eager to see what a pro-business administration that had inherited a healthy economy might yield. They also expected that the president’s impulses for radical economic change might be contained by the stock market itself — a sudden drop might persuade him to change course.

Despite concerns that stocks were highly valued, they continued to climb — peaking in February.

But even before this week’s meltdown, data from EPFR Global showed that investors had pulled $25 billion out of funds that invest in U.S. stocks in the two weeks through Wednesday, when Mr. Trump announced the tariffs. Since then, J.P. Morgan has raised its odds of a recession over the next 12 months to 60 percent, Deutsche Bank slashed its forecast for the American economy this year, and others across Wall Street have lowered growth expectations and raised inflation forecasts.

Investors have also sharply raised the odds of more interest rate cuts this year, foreseeing a need by the Federal Reserve to step in to prop up the economy. The selling on Wall Street erased $5 trillion in market value from companies in the S&P 500 in just two days, according to Howard Silverblatt, senior index analyst at S&P Dow Jones Indices.

As bad as the recent drop in the S&P 500 was, other market measures are in worse shape. The Russell 2000 has lost a quarter of its value since its November peak. The Nasdaq Composite, which is loaded with tech stocks that were hammered this week, is down nearly 23 percent from its December peak.

“It’s saying this is really bad,” said Liz Ann Sonders, chief investment strategist at Charles Schwab. “This exceeds anything I saw on anybody’s worst-case scenario. This did more to dent animal spirits, which had been something that had revived in the immediate aftermath of the election.”

Dan Ivascyn, chief investment officer of the large asset manager PIMCO, said the tariff announcement this week represented “a massive material change to the global trading system” and would lead to “a material shock to the global economy.”

“In recent decades, economics has tended to drive political decisions,” he said. “We may be entering a period where politics drives economics. That’s a very different environment to invest in.”

Some said Mr. Trump himself offered a precedent. In 2018, he imposed tariffs on global steel and aluminum imports, solar panels, washing machines, and $200 billion of goods from China. But those levies pale in comparison with what was rolled out on Wednesday, and the effect on markets was far more muted.

Though Mr. Trump had always promised to use tariffs again in an effort to restructure the American economy — bringing manufacturing back within the country’s borders and making the United States less dependent on foreign trade — the scale of the policy shift caught investors, economists and business leaders off guard.

The new taxes raised the average effective tariff rate on U.S. imports to a level not seen since the 1930s, analysts at S&P, the ratings agency, said.

Some investors hold out hope that the tariffs are just a starting point for negotiations that will bring them down over time.

But while Mr. Trump has suggested that he is open to negotiating tariffs with other countries, China has already reacted by matching his additional 34 percent tariffs. Canada swiftly introduced tariffs of its own, and Europe is also expected to respond.

“The base line is so high right now that even well-negotiated tariffs are going to be high,” said Adam Hetts, global head of multi-asset at Janus Henderson Investors. He feared that the damage had already been done.

“The damage is done because tariffs now have teeth, and consumer and company behavior is already starting to change,” Mr. Hetts said, echoing a fear held by other investors, too — that the tariff talk has already chilled business and consumer activity.

Few chief executives have spoken out about the tariffs, but those who did expressed alarm.

As the tariffs were announced, Gary Friedman, the chief executive of the furniture retailer RH, was on an earnings call with investors. He was heard cursing, after checking RH’s share price. RH gets many of its products from Asia, Mr. Friedman explained.

On Thursday, Sean Connolly, the chief executive of Conagra Brands, told analysts that the food company was trying to keep up with the sudden shifts in tariff policy.

“Things are moving around not only on a weekly or daily basis but on an hourly basis right now,” he said.

From the White House, however, the message is one of exuberance — if investors just have the patience to see it through.

“The markets are going to boom,” and “the country is going to boom,” Mr. Trump said on Thursday. Howard Lutnick, the secretary of commerce, said during an interview on Thursday that “American markets are going to do extremely, extremely well” over the longer term.

History shows that even the worst market crisis will come to an end, once investors are satisfied that prices have fallen far enough to reflect the new reality, or another shift in policy gives them reason to start buying again. On Friday, a report on hiring in March that was far stronger than expected, showing that the economy was still on a solid footing last month, failed to stoke a market recovery.

Business leaders have responded to surveys saying they intend to slow plans for their own investments. Executives at airlines, banks, retailers, energy companies and more watched their companies’ valuations drop this week. Consumers, after trying to get ahead of the tariffs on some big-ticket items, have said they intend to spend less, too.

“I’m not sure what we got gives companies a lot of confidence,” Ms. Sonders of Charles Schwab said. “I think it doesn’t alleviate that component of uncertainty.”

#Investors #Recoil #Trumps #Pledge #Remake #Global #Economy